Gambling, Scorsese, other recommendations

When to hold 'em, when to fold 'em, and when to eat at Benihana (never again, birthdays not excepted).

Two Sunk Thoughts posts in less than two weeks is what’s referred to as a black swan event. Seeing another edition of this newsletter sprout up in your inbox so soon after you deleted the last one should serve as a reminder that life is what happens when you’re busy plotting normal distributions.

Randomness will be the organizing principle of this month’s roundup. The books and movies listed below all deal with games of chance. Appropriately enough, the first item on the list came to my attention when I won the lottery that is the Houston Public Library’s book hold system.1

Gambler: Secrets from a Life at Risk

I would have placed a hold on this memoir by professional sports gambler Billy Walters at the time of its August publication, after reading one of the news stories covering its sensational claim that golfer Phil Mickleson had bet over $1 billion, including on a Ryder Cup match he was playing in.

By the time HPL notified me that my copy was available for pickup, I had forgotten ever requesting it. Then I read it in a day and subsequently forgot most of the details, but in a way that’s exactly what you’re looking for in a book largely devoted to decades-old stories about big wins, bad beats, and boozing.

The basic arc of Walters’ life story goes like this: teenage pool hustling in Louisville; twenty five years of functioning alcoholism marked by bankruptcy, divorce(s), and periods of great success as a used car salesman, real estate developer, and illegal bookmaker; thirty five years in which Walter’s risk loving ambition is institutionalized and productively channeled into an international sports betting operation; a stint in prison for insider trading; wistful reminiscence. To distill this into a single thematic statement, Gambler tells the story of one man’s journey to self-realization through the Kelly Criterion.2

Sizing bets is tricky, even when the expected value is positive.3 Most people bet too much (though some have their reasons). In one well known experiment, a group of college economics students were each given $25 to make even-money wagers on a series of coin flips that had a known 60% probability of landing on heads. The students could play for 30 minutes (app. 300 flips), and their winnings were capped at $250.

Mistakes were made:

“Only 21% of participants reached the maximum payout of $250, well below the 95% that should have reached it given a simple constant percentage betting strategy of anywhere from 10% to 20%. We were surprised that one-third of the participants wound up with less money in their account than they started with. More astounding still is the fact that 28% of participants went bust and received no payout. That a game of flipping coins with an ex-ante 60/40 winning probability produced so many subjects that lost everything is startling.”

Gambler adds some wrinkles to our understanding of bet sizing theory.

For one thing, although the Kelly Criterion teaches us to keep things simple and bet a constant percentage of our available funds, “availability” turns out to be an elastic concept for gambling addicts. Walters has multiple stories from his early days of betting and losing 100% of net worth, and then some. This works out fine though. The sort of person who becomes your creditor after cleaning you out in a backroom poker game one night is also the sort of person likely to become your debtor after one more night at the table.

As Walters refined his strategies / curbed his addictions, the problem switches from knowing how to limit his bet to the optimal amount (say, 20% of his bankroll on an even money wager with 60/40 probability) into figuring out a way to actually bet that full amount. Walters may or may not be “widely regarded as the Michael Jordan of sports gambling,” as the book’s cover states, but if he is, then he earned that title less for some novel method of handicapping than for his ability to put large sums of money in play when the odds were in his favor.4 Walters might bet several million dollars on a Super Bowl number he likes, but struggle to place $50,000 on a regular season NBA game.5

One of the best parts of Gambler is Walters’ explanation of how to orchestrate a troupe of runners to front bets in ways that:

A) Don’t reveal to the sports book that there’s sharp money behind the bet, creating a risk of the bet being rejected and/or the account closed.

B) Don’t move the line, or better yet, that do move the line because what you really want is to take a larger position on the opposite side.

C) Don’t end up with the runner - most likely a degenerate small time gambler willing to spend all day waiting by a payphone in a smoky casino - either front running your bet, leaking it to a rival, or just screwing it up.6

The spread of legal online betting increases market liquidity, but also makes it easier for sports books to monitor accounts and restrict the ones that have won or could win too consistently.

There’s no shortage of critics of ubiquitous online gambling, and Walters is perhaps the most unusual: he argues (sincerely and convincingly) that limits on wager amounts are an affront to the American tradition of risk taking and efficient markets.

Casino

When you’re sitting on a plane and doing your best to tune out the FAA mandated safety announcement, Casino is not the movie you expect to see nestled between Cars 2 and Chocolat on the list of in-flight entertainment options.

It’s not that Casino is the most inappropriate thing to watch on a crowded plane. United 93 comes to mind, and even within the narrow category of “Las Vegas-set films released in 1995,” Showgirls takes the top spot. Nonetheless, a strange choice here by Delta.

Incidentally, Anthony “Tony the Ant” Spilotro, the real life inspiration for Joe Pesci’s psychopathic, fellatio-addled Mob enforcer makes several cameos in Walters’ Gambler. Carl Icahn does too.

On this rewatch I discovered that the movie’s title holds its key. Watching Casino feels like being at a casino. It’s exciting and exhausting; glamorous and seedy; sprawling, claustrophobic, unpleasant. Despite all the excess, Casino strikes us as a thin movie - Goodfellas reheated and diluted by a three hour runtime.7

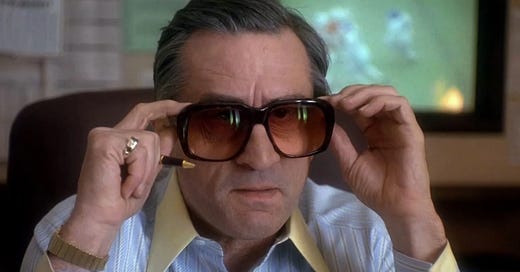

The sunglasses though.

I’ve been told that the French consider Casino to be Scorsese’s masterpiece.

The Color of Money

The obvious but incorrect double feature pairing for The Color of Money would be The Hustler. That existential pool hall drama from 1961 is indeed a classic, but ultimately unnecessary to appreciate what Scorsese was up to when he agreed to direct this sequel a full 25 years later.

The Wolf of Wall Street is a better choice on our hypothetical double bill because it provides an interesting comparison of how Scorsese matches style and subject. Some people criticized Wolf for glorifying white collar criminals. This led others to defend the film by coming up with an even stupider take: it was a devastating and timely critique of the system that had produced the Great Financial Crisis five years earlier.

I don’t believe Scorsese cares much about Jordan Belfort either way. He certainly doesn’t care about the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, TARP or any of that acidic, above the shoulders, mustard shit. What he does care about is vitality and how to capture it on film - with whip pans and swooping tracking shots, with cacophonous soundtracks, dance sequences, slapstick physical comedy right out of Looney Tunes … all of this, and then some.

Contemporary responses to The Wolf of Wall Street ignored how Scorsese was using a battering excess of style to make the case for the supremacy of aesthetics over whatever other concerns they might try to burden the film with.

The Color of Money was also bound to be misunderstood. Conventional wisdom is that this was the proverbial “one for them” that Scorsese had to do while raising funds for his long gestating passion project, The Last Temptation of Christ.8 And though it pains me to look back on an era when an auteur selling out meant directing a contemporary drama starring Paul Newman and Tom Cruise rather than, say, a $150 million self-flagellating doll commercial, you can see why The Color of Money would be politely received as minor-Scorsese.

Sure, the film won Paul Newman his make-up Oscar, and critics didn’t have to reach too far to find meaningful things to say about aging, fading masculinity, the disappearance of a certain American way of life. But let’s not out think ourselves here:

There’s plenty of exuberance in The Color of Money, but even more restraint. (And not in the sense that “restrained” is used as a synonym for “slow” or “boring” or any of the other words that critics are unwilling to admit best describe The Irishman and Killers of the Flower Moon.) It’s a low stakes movie that is literally about low stakes: the plot narrowly revolves around a veteran pool hustler’s attempts to teach his young protégé how to restrain his natural arrogance and carefully titrate his displays of skill until the opportunity for a truly big score presents itself.

In film as in real life, bet sizing matters. Sunglasses too.

Also:

As luck would have it, The Hustler is currently streaming on Hulu. This one actually makes for a good double feature with Casino: Jackie Gleason’s unexpected turn as the champion pool player Minnesota Fats would later be echoed by Don Rickles playing a no nonsense pit boss.

Paul Newman is extraordinarily handsome in this movie, but it’s George C. Scott who stands out as Bert Gordon, the Mephistophelian stakehorse who pushes Fast Eddie Felson to win at all cost. Who among us hasn’t failed to seize the moment because we were too busy “waitin’ to get beat … deciding how [we] were gonna lose?” A discomforting thought that reminded me of an excellent essay by Cedric Chin on playing to play vs. playing to win.

The Super Bowl is of course the Super Bowl of sports betting. The world’s biggest celebrity looms over this year’s event, which is why it’s so important to remember what Sam Kriss uncovered in this shocking piece of investigative journalism: Taylor Swift does not exist.

Speaking of non-existent pop stars, Milli Vanilli puppet master Frank Farian died this January. These days people seem less cool with the idea of a German guy whose father fought for the Nazis creating not one, not two, but three different pop groups where people of color danced around and pretended to sing songs he recorded for them. But those songs do slap. Youths agree. So does historian Simon Sebag Montefiore, who described the Farian-penned Rasputin as “an excellent introduction to Russian court politics of the early 20th century.”

The above discussion of the Kelly Criterion was inspired by my reading The Missing Billionaires by James White and Victor Haghani. Byrne Hobart’s piece in his Capital Gains newsletter is a good introduction.

Houston's sprawl and humidity, though formidable, are somewhat overstated as negative quality of life factors. Higher on my list would be the whimsical municipal trash pickup schedule, sidewalks that are only intermittently walkable, and a public library catalog that is simply much smaller than you'd expect in a city of 2.3 million people. But complaining that Houston isn't Copenhagen would be to miss what makes the city great.

This is explained on the linked Wikipedia page, but for those of you adverse to opening additional tabs, the Kelly Criterion is a formula for determining what percentage of your funds to wager on a series of bets with known payout and known probabilities of success/failure in order to maximize long term wealth.

Rather, sizing bets is tricky only when the expected value is positive. When it’s negative, the optimal amount to bet is pretty clearly zero

Walters and his team were great handicappers though. He was an early adopter of computerized analysis for sports gambling, and demonstrated an ability/willingness to find new strategies when the alpha from old ones began to decay. But things were simpler in the early days: in pre-internet, pre-ESPN seventies, Walters could derive an informational edge by paying the plane cleaners at Las Vegas McCarren Airport to collect the various sports sections from local papers left by tourists.

His largest bet mentioned was $3.5 million on the New Orleans Saints in the 2010 Super Bowl. The Saints covered as 4.5 point underdogs against the Indianapolis Colts. They won the game too, 31-17, though that didn't matter for Walters’ purposes.

"Did you say lay the points or take the points in Denver?"

Of the countless Goodfellas imitators, Boogie Nights gets the best of my love.

That’s a pretty good passion project/play pun by the way.

This one was on my level which I appresh