This is a longer post than usual and might get cut off by your email provider. Your best bet is to delete it without reading. Second best would be to open it in a browser or the Substack app.

My Christmas gift to Sunk Thoughts subscribers was to let the extended holiday season go by without an edition of this newsletter polluting your inboxes. To pass the days before I could subject you to another string of barely coherent musings, I went on a trip to Japan.

I was miserable the entire time.

Don’t get me wrong: as far as vacations go, this one was essentially perfect. Each bite of food was the best I ever tasted. Everyone I met was unfailingly hospitable. The trains were always on time, the scenery varied and fascinating.

But my ability to take pleasure in any of this was undermined by the fact that my traveling companions didn’t once ask me to do the thing I so desperately wanted to do - to explain things.

Before getting on the plane to Tokyo, I had read several books about Japan. A few of them I even finished. All of these efforts turned out to be for naught. What good is it to learn about a culture different from your own if you can’t impress people with the extent of your learning?

Like, it would obviously be a missed opportunity to travel to Japan and not seek out sushi. I’d argue that it would also be a missed opportunity to travel to Japan, seek out sushi at the world’s largest fish market, and then tell your husband that you’d prefer to savor that sushi in silence rather than listen to him speculate about the reasons why the tuna auction is conducted using an English instead of a Dutch or a sealed bid second price format. My wife disagreed, as she did with my attempt to enrich our sunrise walk through the Meiji Jinju gardens with a comparative analysis of the invention of State Shinto in the late 19th century and Christian nationalism today1.

OK, fine, I thought. Americans are notoriously provincial. Perhaps the Japanese themselves would be more willing to engage. I knew from my extensive reading that this formerly isolated island nation had prospered greatly after opening itself to the dynamic forces of the West.

I wasn’t expecting the full Cheap Trick at Budokan treatment, but I was hoping that at least one person on the street would recognize me as the author of a infrequently published, finance adjacent Substack and ask me about the yen carry trade.

The thing is, if you read several books on Japan - as, again, I have - then you’ll know that the Japanese people are complicated to the point of contradiction. To quote one of the most influential of those books, they are:

“Both aggressive and unaggressive, both militaristic and aesthetic, both insolent and polite, rigid and adaptable, submissive and resentful of being pushed around, loyal and treacherous, brave and timid, conservative and hospitable to new ways.”

-Ruth Benedict, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword (1946)2

I’m sure that my Japanese hosts wanted to have me explain their history and economy as only someone with the gift of an outsider’s perspective could, but some countervailing cultural norm prevented them from asking. It’s also possible that they actually did ask and I misunderstood because my outsider’s perspective prevents me from learning any of their language. The Orient is mysterious.

My flight to Tokyo arrived on time, but I knew before stepping off the plane that I was 40 years too late. It was the 1980s that I wanted to visit. This was the boom times for Japan - and for white dudes writing about the nation’s unstoppable march to world dominance.

This was the era when Toyota and Honda, Hitachi and Panasonic ran roughshod over the competition. Rockefeller Center and its Christmas tree had fallen into the hands of Mitsubishi. The unemployment rate in Detroit reached 127%. Bruce Springsteen wailed for the Rust Belt on Born in the USA; shortly thereafter, his record label was bought by Sony.

The pervading sentiment in America was one of wounded nostalgia. We used to make things in this country. Back then we’d start building a battleship on Monday, and by Thursday we’d be whacking that puppy with a bottle of champagne and sending it over to Tokyo Harbor so that General MacArthur would have a decent place to sit while he accepted the Emperor’s unconditional surrender.

By the eighties though, Americans were incapable of producing anything other than explanations of much more capable the Japanese were. We’d fallen behind in steel and autos, and by the inescapable Ricardian logic of comparative advantage, there was nothing left to do but churn out books with titles like Zen and the Art of Lean Manufacturing. It’s analogous to how the British had once ceded global hegemony to the US but nonetheless managed to find a nice little niche in the value-added cultural production sector by importing records by American R&B artists and re-exporting ones by the Rolling Stones.

In this story, Japan took about forty years to go from vanquished to victor.3 That’s roughly a double speed playback of the time that elapsed between when Commodore Perry’s black ships forcibly opened the Tokugawa Shogunate to American trade and when Japanese dive bombers appeared in the skies above Pearl Harbor. In both cases, the story didn’t end there. Or end well.

We know that history doesn’t repeat itself so much as deplete itself through progressively less inventive sequels. It should be no surprise then that both pre and post war Japanese history followed a rise and fall pattern - and that second go round was, mercifully, not as spectacular as the first. “Boom” and “bust” are metaphors used to describe the last decades of the Japanese 20th century; in the time of Hiroshima, these words had a more literal meaning.

A chart of prices for central Tokyo real estate from peak to trough looks apocalyptic, but of course there’s no real comparison to actual devastation visited upon these assets (a euphemism if there ever was one) within living memory. And yet, it’s not entirely inaccurate to say that the paper losses of the post-bubble era have proven more damaging than the real losses suffered during the war - that a country can quickly recover from all of its buildings being leveled, but not from all of its savings being spent servicing debt on buildings whose values have fallen. Slowly then all at once, the vibes shifted. Japan had struck fear into policymakers around the world with its singular mix of economic discipline and collective spirit, but no sooner had it caught the West than it became frightening for different reasons. Japan was aged, atomized and indebted. In other words, it looked a lot like us.

At this point in the analysis, a higher quality newsletter would present a collection of data to illustrate Japan’s latter day economic stagnation - shrinking real wages, non-existent growth in GDP and worker productivity, the highest levels of government debt in the world, etc. Long time Sunk Thoughts readers will know better than to expect any of that here. I’m too lazy to shape an argument with data, it’s true. But it’s also true that Japan’s economic predicament has an amorphous quality that resists easy classification.

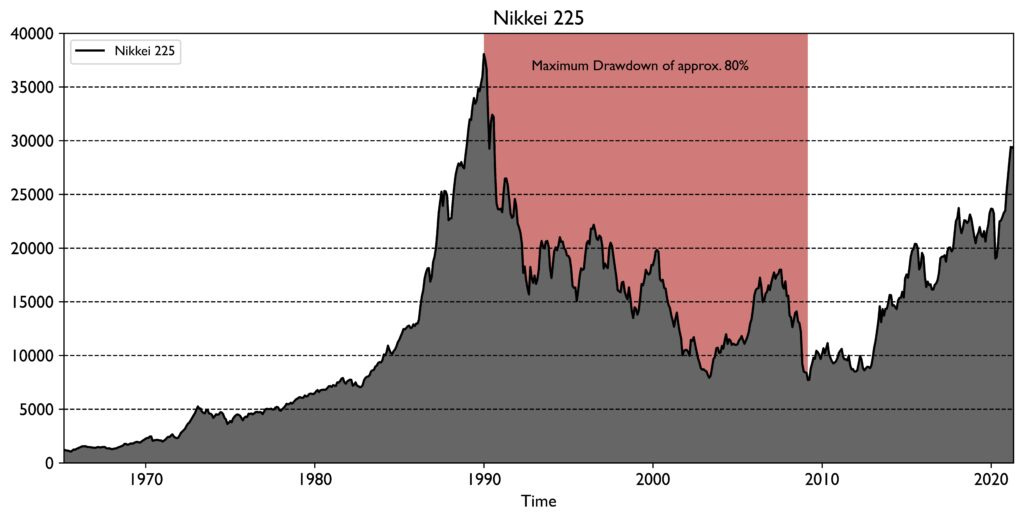

What was at first called the Lost Decade turned into the Lost Decades. How many decades exactly? No one seems to know. Definitely more than two. (The Global Financial Crisis upset whatever momentum Japan had built in the 2000s.) Arguably less than three (see the partial success of Abenomics in the 2010s). Or perhaps there are more Lost Decades to come. (Despite some encouraging signs in the form of moderate inflation and the Nikkei returning to highs last reached in 1989, Japan’s growth outlook remains challenging.)

If the Japan of 2025 is no longer the poster child for prolonged economic malaise, it’s got less to do with an improvement in fundamentals than it does the emergence of other countries facing similar challenges. South Korea has a lower birth rate. China has deflation and a massively insolvent real estate sector. Europe’s population isn’t quite as old, though the continent seems committed to following Japan’s historic example with restrictionist immigration policies and dependence on foreign energy.

Then there’s the US. It’s not that we’re immune to the problems of which Japan has long been seen as a harbinger, just that they’re overshadowed at the moment by a widely held belief in our towering exceptionalism that, fittingly enough, recalls how Japan was discussed during its ascendency.

It’s beyond the scope of this What I Did on My Winter Vacation essay to argue whether this time really is different. Whether the American behemoths that dominate the market cap rankings really have discovered a secret sauce more potent than the high fructose corn syrup that once fueled Japanese companies on their way to becoming seven of the top ten most valuable in the world. Whether the US equity markets accounting for nearly 70% of global market cap is a more sustainable equilibrium than it was for Japanese ones to account for over 40%. Whether a run up in real estate prices can be followed by one in interest rates and not lead to pain.

Merely posing those questions is enough to give the impression that I expect a Japanese-style reversal ahead. Quite the opposite, or rather, not exactly the opposite but also not not the opposite: it’s all far too complicated to be explained in an unpaid Substack.4

For my purposes, what’s most interesting about intersecting trajectories of Japan and the US is how little bearing any of the above facts - stylized, admittedly, but still recognizably factual - have on the experience of a tourist. You can get in your car in Houston, drive to the airport, fly to Haneda International, hop on a train, walk to your Airbnb, spend the next 10 days exploring Tokyo and outlying areas, and come away none the wiser that you’ve visited a much country that’s much poorer than the one you call home.

I found this hugely disappointing. It’s not that I wanted Japan’s lower relative income (65% of the America’s on a purchasing power adjusted per-capita basis, down considerably from around 85% in 1991) to express itself through conspicuous signs of deprivation. But it would have been quite useful if it had, because like all humans, I have a hard time truly apprehending the power of exponents.

I’ll elaborate. My ancestors who were alive around 1750 were just about as miserable as all my other ancestors who had ever lived before them. The first 300,000 years in my homo sapiens family tree had yielded a scattering of proto-mes who managed to travel more than a day’s walk from the place where they were born, and a few more who learned how to read. Then something changed, and 300 years later, not only can I travel to the other side of the world if I want to, I can write overly long essays about the experience for strangers to read on the internet. The reason is simple: sustained economic growth that compounded at a rate of approximately 1.5% per person per year.

The Japanese postwar miracle distilled the story of modern human progress even further: decades, not centuries, to go from starvation conditions to one of the richest nations ever known. It’s almost impossible to comprehend the scale of the accomplishment, but one way to try would be to observe what happens when things go into partial reverse. 10% annual growth slows to 5%, then 3%, then something breaks - the numbers start flickering with negative signs, then refuse to budge above the 1% mark. What does that look like? I wanted to know.

I went to Tokyo so I could gaze upon the ruins of a once great city and finally understand on a visceral level what happens when modern society takes its foot off the gas. I wanted abandoned skyscrapers, empty school yards, grey haired salarymen eating silently on their own. While the tourists were busying themselves taking photos of torii gates, I would look for the real Japan, a nation that had launched itself so successfully into the modern world that it overshot and landed in a dystopian version of the future waiting for us all.

The first person to challenge my thesis was a child. A group of children actually. I had assumed these things didn’t exist in a country with the highest median age in the world,5 but then here they were, walking down the sidewalk in adorable matching hats.

A little unnerved by this sighting, I ducked into one of Japan’s many 7-Elevens for a restorative snack. But when I went to check out, I was confronted with more surprises. The man working the register was visibly American, in the sense that he was an immigrant from somewhere in South Asia. That’s our thing, I thought. Japan doesn’t do foreigners.6 I tried to put this out of my mind as I dug around in my pocket for a 100 yen coin (I knew that although Japan was once lauded for technological innovation, it was still heavily dependent on old-fashioned technologies like cash and fax machines) only to see a message appear on the payment terminal - in English no less - that Visa was accepted.7

The rest of my days in Tokyo were an exercise in disillusionment. Near Yoyogi Park I saw a man jaywalking - so much for the myth of Japanese obedience. In the luxury shopping district of Aoyama, I noted that the starchitect-designed emporiums were new builds, and not, as I assumed they would be, white elephants preserved in amber since the boom years. Even Japan's famous vending machines were of less symbolic value than I hoped for. There were a lot of them, sure, and it was a neat trick that they sold drinks both hot and cold, but where were the machines selling used school girl panties? I wasn't looking for souvenirs, just confirmation of my theory that the transition from living in a high to low growth economy did strange things to men's souls.

Most of all though, I was worn down by the sheer pleasantness of the place. I’d been told in advance about the litter free streets and walkable neighborhoods, so these weren’t too great of shocks. But the widespread availability of usable public restrooms made my heart sink.8 I felt as though I were an executive at the American Motor Corporation who had come to a big auto show to promote the latest model Gremlin only to be outshined by something called the Honda Civic. Let’s pack it up and head back home, boys: America’s over.

My extraordinary talent for observation and analysis is a double edged sword. Obviously, it means I’m capable of producing works of searing insight. Less obvious to those without such gifts is the fact that it can be quite lonely to perceive the truth of some great matter when no one else can. So it came as a great relief to find out that at the very moment I was wrestling with the question of how to measure societal wellbeing - with GDP per capita, or bathrooms per capita? - one of the world’s preeminent economics bloggers was doing the same.

Noah Smith’s post takes as its starting point my observations about Japan. Not literally mine, but those of many visitors like me who are at a loss to explain how much better the quality of life there seems to be. It’s an excellent overview of factors that make it difficult to compare national living standards (e.g. different number of hours spent on work, leisure, domestic work, and commuting; different health profiles; adjustments for local prices of non-tradable goods), as well as a reminder that visiting Japan as a tourist is not the same as experiencing what life is like for locals. Noah has another post on the broader topic of how much you can learn about any place from traveling there; Dwarkesh Patel’s recent trip to China had him asking the same question.

I’d recommend all those posts. I’d also say, if asked myself, that traveling somewhere is a relatively inefficient way to learn about living in that place specifically, but one of the best ways to learn about living in 2025 generally.

For instance, during our trip my group relied on Google Maps to navigate with incredible precision. It helped us locate restaurants hidden down alleyways and up several flights of stairs, drive around a rural island with unmarked roads, and wait at the exact location on the subway platform that would ensure the car that we boarded was the one that would deposit us closest to the exit when we reached our destination station.

At the margin I would have preferred we got lost more often, since wandering around an unfamiliar place is pretty much what we came to Tokyo to do, and constantly staring at my phone meant I never developed a feeling for the city’s orientation. But I did hear from several people that the practically flawless experience of using Google Maps in Japan today is remarkably better than it was just a few years ago. I wouldn’t have said that I’d noticed a noticeable difference in Google Maps’ quality in the US over that time period. Does that say something about my inability to register incremental improvements? Or possibly something about Google’s rate of overseas market penetration and investment? Have GPS satellites gotten a lot better? Ultimately I don’t really care, other than to make the point that in place of local knowledge, travel in the 21st century offers a chance to rethink the things you thought you knew about the wider world.

I mentioned earlier that Americans are provincial. I’m no exception. After arriving in Tokyo, I needed less than a day to finalize my overarching explanation of the country’s past, present, and future. The rest of the trip I spent thinking about life back home.

What would a first time visitor to America make of the place? Even after accounting for the idiosyncratic factors that predisposed me to find Japan an altogether more attractive destination (it was a novel experience; the exchange rate was favorable; I really like fish products), I couldn’t dismiss the feeling that someone who visited here first would find America to be a disappointment.

Tokyo is one of humanity’s greatest accomplishments. 41 million people in the metropolitan region, 236 Michelin stars, next to zero crime. Though the Japanese Century never quite materialized, as the capital of a would-be empire, Tokyo surpasses Rome, London, or Tenochtitlán. Monumental in the aggregate but wonderfully human-scaled throughout, it’s an endlessly fascinating and enjoyable maze for a visitor to navigate - a neon-lit floating world more impressive than just about anything else we could present to a time traveler from the distant past who showed up in the twenty first century and asked, “what do you have to show for yourselves?”

Surely the time traveler would assume the city he was gazing upon was part of the richest and most powerful nation around. After you gently corrected him and agreed to take him somewhere in the actual richest and most powerful nation around, where should you go?

America’s leading cities would come as a disappointment. Compared to Tokyo, even New York is small. Plus it’s dirty and loud and the pizza isn’t as good. You could take a different approach and take him somewhere that represents the rugged beauty of the American continent: Yosemite National Park, or the Bakken shale formation perhaps. The Las Vegas Sphere is always a possibility, but what if the time traveler doesn’t like the Eagles?9

I was consumed by this hypothetical while on my trip. By the final days I had all but stopped caring about seeing any more of Japan. I still dragged myself to museums and temples and exquisitely relaxing onsens, but the whole time I was turning over the question: America, what do we have to show for ourselves?

Eventually, two plausibly compelling options came to mind.

The first would be a suburban Costco in any third tier US city. Milwaukee, Raleigh, Indianapolis - doesn’t matter. I might ask the time traveler to spin around in circles and then stick his finger on a random spot on the map to really drive the point home: such is the wealth of America that even our minor settlements have warehouses piled with frozen prime rib and flat screen televisions, double ply toilet paper and chili-spiced trail mix.

The second wouldn’t be location dependent. (San Francisco would work as well as anywhere else, although after visiting Tokyo, the time traveler probably wouldn’t take a foggy seaside village to be the city of civilizational greatness that it is. But he might appreciate the chance to eat more sushi in Japantown. Maybe he’d recognize the Golden Gate Bridge’s international orange paint as the same shade used on the Tokyo Tower.) All I’d need for this demonstration is an iPhone and some patience as I tried to explain to the time traveler how my home country was the most dynamic on earth. We’d invented this magic device, for example, which sure, has a smaller screen than the electric displays of Shinjuku, but could do a lot more.

We’d look up photos. Here’s a man on the moon. Here’s the Hollywood sign. We’d look up facts. Here’s a ranking of countries by average life expectancy: we don’t come off so hot on this one, but you have to believe me when I say we’re also the best at medicine. And so on.

Eventually I’d navigate us to one of the AI apps. You might not understand this at first, I'd say to the time traveler. A lot of people don’t. I’m not sure that I really understand it, but what it is, or what it could turn out to be, is … what’s the best way to explain this? … it’s sort of like an all knowing, infinitely replicable Machine God that will either kill us all or lead to even more unimaginable technological breakthroughs, like time travel.

Then he’d nod and ask to go back to Tokyo.

Both terms were coined by outside observers and have disputed meanings.

I didn't get around to making this related point in my otherwise comprehensive monologue that day, but I wonder why in the midst of renewed interest in the cultural Christianity (not just Jordan Peterson videos, but also in the godless failing New York Times), there's been so little discussion of Japan.

Japan is an exemplar of what might be considered the religion without belief model. Shrines and temples are sprinkled around every city, beautifying the landscape and providing opportunities for people to pop in around the holidays for blessings. It's a syncretic tradition - people are said to "be born Shinto and die Buddhist" due to the ceremonies observed on either occasions - that places a vague but genuinely useful emphasis on things like family, duty, nature, and self-control.

I'm quite sympathetic to those looking to promote the social utility of Christian virtue in modern society, but pessimistic about the likelihood of achieving their desired outcomes. Just because something is useful doesn't make it true, and that really seems to matter when it comes to leveraging belief as an engine of social change. Japan, where within living memory there's been an official effort to integrate traditional religious beliefs into a governing ideology, and where as far as I can tell there seems to be a high level of ambient religious culture and low level of actual faith, is in many ways a more harmonious and cohesive society than the US. But in others ways it's clearly worse off: fewer marriages, fewer children, more suicides, to say nothing of sui generis manifestations of isolation like hikkomori and johatsu. That should lead us to revise downwards the gains to be had from posting the Ten Commandments in public schools.

Here’s a quote from another book, Max Hasting’s Retribution, which I submit as the most Japanese thing ever:

“[Kamikaze pilots’] parting instructions decreed blandly: ‘Once you take off from here, you will not be coming back; you must leave your effects in an orderly state, so that you will not make trouble for others, or invite mockery.’ ’”

There were forty years to the month separating the signing of the instrument of unconditional surrender on the deck of the USS Missouri and the signing of the Plaza Accord in September 1985 - in some ways was the high water mark for Japanese strength. While the agreement was designed to depreciate the dollar against a wider basket of global currencies, the US's largest bilateral trade deficit by far was with Japan.

In other ways though, the Plaza Accords were a sign and a source of Japanese weakness. Japan's export led postwar growth had been enabled in no small by the US's open market and forbearance toward an artificially weak yen - to say nothing of the US defense guarantees - so it was in no position to decline when its most important ally asked it "voluntarily" allow its currency to appreciate.

Which it did. Which led the Bank of Japan to fend off an economic slowdown with a series of interest rate cuts. Which fueled a massive asset bubble. Which deflated. Which Japan has never really recovered from.

I'll put it this way. I'm still in the market and not trying all that hard to reduce exposure to US megacaps, despite the S&P 500's having a cyclically adjusted P/E ratio last seen before the 2022 market downturn, and before that during the Dot Com bubble. The modal return scenario I expect for the next decade is indeed disappointing (say, 5% annually), but I don't have an exciting way to trade this. I mentioned earlier that I'm lazy, so take this with a grain of salt.

As for the analogy with Japan, the more I read about their late eighties bubbles in stocks and especially property, the more it seems to be qualitatively different than whatever's happen today. Boom and Bust by William Quinn and John D. Turner has a good, chapter length overview of the causes and consequences of the Japanese bubble.

If you don’t include Monaco. Which I don’t.

They're working on it though. Sort of. From 2000 to 2023, the foreign born percentage of Japan's population doubled from a very low baseline of 1.34% to 2.7%. In Tokyo, 10% of residents in their 20s are foreign born.

An earlier version of this essay included an extended analogy between the 1858 Treaty of Amity and Commerce which forced Japanese ports to open to Western trade, and the interchange rates merchants pay as a consequence of the relentless global expansion of American owned card networks.

To the extent that this essay has a topic, it's the uniquely American variety of cognitive dissonance that arises from knowing you live in the richest society in history, traveling to another country and finding it to be a more refined, frankly nicer place to live, and yet (this is crucial) understanding on some level that for all the waste and want that exists in your home, there's no place you'd rather be.

But on the topic of public restrooms, the German director Wim Wenders (himself no stranger to American myths - see Paris, Texas) took a more straightforwardly romantic view of life in another country with Perfect Days, his 2023 film following the simple joys experienced by a toilet cleaner in present day Tokyo.

He'd be in good company:

Stomping on the moon will be for sure be a hard one to top.

My impression of the dunk contest is that the athleticism of the dunkers has almost certainly gotten better over time, but interest in the event has waned (including among the superstars who sit it out). I wonder if since the moon landing there's been the technological equivalent of a 720 between the legs dunk that people more or less shrugged at.

Rewatching Mad Men and near the end. Had the thought: humanity is still "off peak" vis a vis the moon landing, right? I mean, in a humanitarian sense things are much much better than then, but we haven't had anything score quite as high in the dunk contest since then, have we?